You can read an introductory essay here and can download the series from iTunes and elsewhere.

Monday, 29 October 2012

The Anglo-Saxons

You can read an introductory essay here and can download the series from iTunes and elsewhere.

Saturday, 27 October 2012

Mo Yan and the Nobel Prize

There might well be room for debate about this year's recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize but I reckon Mo Yan fully deserved the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Ever since the death of Shen Congwen, China has lacked a serious contender for the prize, mainly because Chinese literature had such a desperate time between 1949 and the late 1970s. During the Cultural Revolution a mere 12 novels were published per year on average but, even before then, Chinese fiction suffered terribly. However, when China began to open up in the late '70s and early '80s, there was also a renaissance of Chinese writing and the greatest author to have emerged at that time was Mo Yan.

(And no, I haven't forgotten Gao Xingjian, who won the Nobel Prize in 2000. I suspect it came as as much of a surprise to him as to followers of Chinese literature both inside and out of the country.)

Arguably Mo Yan's greatest novel was one of his first, Red Sorghum, a great war novel which, like J.G. Ballard's Empire of the Sun, redefines the very way in which we see the Second World War. For a start it reminds us that there was more to the war than what happened in Europe between 1939 and 1945. More significantly, it also challenged Maoist versions of Chinese history, which is why it was originally published by the Liberation Army Publishing House with some rather significant cuts.

I haven't got space here to give a full book review but it's certainly worth a read, though you'd have to tread carefully before teaching it to school children.

Mo Yan often raises deals with topics which are of great interest to Catholics even if the way in which he deals with such topics is often far from Catholic. For example, from as early as his 1986 short story, 'Abandoned Child', through to later works such as the often savagely surreal The Republic of Wine and Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out (perhaps the most readable of his later works), he examines the place of children in modern China, showing a specific interest in children, child abandonment, and adoption.

I haven't got space here to give a full book review but it's certainly worth a read, though you'd have to tread carefully before teaching it to school children.

Mo Yan often raises deals with topics which are of great interest to Catholics even if the way in which he deals with such topics is often far from Catholic. For example, from as early as his 1986 short story, 'Abandoned Child', through to later works such as the often savagely surreal The Republic of Wine and Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out (perhaps the most readable of his later works), he examines the place of children in modern China, showing a specific interest in children, child abandonment, and adoption.

Another common approach in his work is the use of an unconventional family history to challenge conventional Chinese political history. Sadly, he has not always escaped religious prejudice in his attempt to challenge political prejudices. In Big Breasts and Wide Hips, for example, one of the main characters develops a bizarre breast fixation that stunts his emotional growth into adulthood partly because he is the illegitimate son of a cowardly Christian (and possibly Catholic) missionary priest.

Mo Yan's work is challenging in many ways but he's clearly a highly significant author from a country which is going to become culturally as well as politically and economically more important as the century progresses. We in the West need to engage with works like his.

So let's finish, slightly flippantly, with a view from China: it's a real sign of the times when the People's Daily seems to be more interested in how much money Mo Yan is going to make from winning the prize than in his cultural value.

Friday, 26 October 2012

Lord Alton on Tolkien

What's particularly useful is that David Alton offers not only the transcript of his talk but also the accompanying PowerPoint presentation and an audio recording.

Monday, 22 October 2012

Unapologetic

I can't say that the title greatly inspires me - the fact that Christianity still makes emotional sense is neither surprising nor a great basis for belief in my view - but the book certainly sounds intriguing and worth a read even so.

Saturday, 20 October 2012

Hemingway's 47 Endings

A new edition of Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms has just been published. What makes this particular edition a must-have for admirers of Hemingway's work is the inclusion of the 47 alternative endings the author came up with. I, for one, find it tremendously reassuring that a great author like Hemingway should have had so much difficulty (and taken so much care) over his novel's final words.

To hear some of these other endings and an interview with Seán Hemingway, the author's grandson, click here.

Tuesday, 9 October 2012

Newman, Hopkins, the Saints and Literature

Today is the Memorial of Blessed John Henry Newman, the only novelist (I think) to have been recognised as a saint (see here, here, here and here for my earlier thoughts on Newman). Not that his work as a novelist (any more than St Thomas More's work as a writer) was what led to him being beatified.

Newman was an inspirational figure in all sorts of ways even during his own lifetime as I was reminded when I was in the Church of St Aloysius Gonzaga in Oxford this weekend, because not only did Newman preach there but it was also where Gerard Manley Hopkins, who was received into the Church by Newman, was a curate (see also here).

In recent days we have remembered St Francis of Assisi (4th October) about whom the novelist Julien Green (among many others) has written, Blessed Columba Marmion (3rd October) whose Christ in His Mysteries (available here for free in French and here for a price in English translation) inspired Messiaen's Vingt regards sur l'enfant Jesus, and the Holy Guardian Angels (2nd October), whom I mentioned the other day. And that's without even starting on those great writers: St Therese of the Child Jesus and St Jerome.

I should also mention Henry Garnett's The Blood Red Crescent and the Battle of Lepanto in connection with the Memorial of Our Lady of the Rosary last Sunday.

That should keep us going for a while.

Monday, 8 October 2012

Fr Tim Finigan on Evelyn Waugh's 'Vile Bodies'

This Week's Catholic Herald

This week's Catholic Herald is definitely worth getting hold of. There is a fascinating interview with Walter Hooper, C.S. Lewis's personal assistant in the last months of the writer's life, and a good article on Jack Kerouac's rather tortured Catholicism.

However, that's not all. There's a great article by Edward Norman on why he has converted to Catholicism and an interesting series of articles on the documents of Vatican II.

Friday, 5 October 2012

Good to Read

One website that's good to read is goodtoread.org, a parent's guide to children's books. Here is part of what the site's creator says about his approach:

Why another site about children's books? One answer to this is easy: you can't have too much of a good thing. Why have more than one sweet shop on the High Street? They all sell much the same things at much the same price, but perhaps you find the people in this one easier, or the display in that one more appealing. There are many websites that give information about children's books, and there are many people with different tastes in websites.

On another level, this website offers a slightly different approach from the majority: it doesn't assume that a well-structured book with a good spread of vocabulary and a certain depth of subject matter is unquestionably a book any child should read. At goodtoread.org we believe that children and young people can benefit from some guidance as to their reading. This may mean recommending a book especially or discouraging a certain book or author on account of the poverty of style or unsuitability of the subject matter. Especially when a series is popular or often recommended, it might mean going over the subjects presented in the book with your child to make sure the youngster has benefitted from it and not been harmed.

To read the whole page (and it's a page worth reading), click here.

All this sounds very good but the test is what happens in practice. A useful test case might be what goodtoread.org makes of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy so here's the link.

That seems to me to be a very fair-minded, balanced and honest appraisal from a thoughtful Catholic so I'd heartily recommend the rest of the website.

Why another site about children's books? One answer to this is easy: you can't have too much of a good thing. Why have more than one sweet shop on the High Street? They all sell much the same things at much the same price, but perhaps you find the people in this one easier, or the display in that one more appealing. There are many websites that give information about children's books, and there are many people with different tastes in websites.

On another level, this website offers a slightly different approach from the majority: it doesn't assume that a well-structured book with a good spread of vocabulary and a certain depth of subject matter is unquestionably a book any child should read. At goodtoread.org we believe that children and young people can benefit from some guidance as to their reading. This may mean recommending a book especially or discouraging a certain book or author on account of the poverty of style or unsuitability of the subject matter. Especially when a series is popular or often recommended, it might mean going over the subjects presented in the book with your child to make sure the youngster has benefitted from it and not been harmed.

To read the whole page (and it's a page worth reading), click here.

All this sounds very good but the test is what happens in practice. A useful test case might be what goodtoread.org makes of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy so here's the link.

That seems to me to be a very fair-minded, balanced and honest appraisal from a thoughtful Catholic so I'd heartily recommend the rest of the website.

Tuesday, 2 October 2012

La Porte des Anges

I was going to save this post for a little while but given that Saturday was the Feast Day of Saints Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels, yesterday was the Feast Day of St Therese of the Child Jesus, and today is the Feast Day of the Holy Guardian Angels, it seemed appropriate to post it now.

La Porte des Anges is a wonderful French language series of fantasy novels for children of 12 upwards. Le Complot d'Ephese starts with a 15 year old boy, Jean-Baptiste, unxpectedly witnessing a fight between the Archangel Michael and a demon in his back garden. They are fighting over a boy (who turns out to be Eutychus, the boy who fell asleep and out of the window while listening to St Paul) and, when interrupted by Jean-Baptiste, drop an old nail, which turns out to be not only one of the nails that held Jesus to the cross but a key to la porte des anges.

It's action-packed, fast moving, often funny, and jam packed with angels; I'll post a full review when I've got to the end.

What is fascinating is that this sort of book should exist at all. The author draws upon a range of sources to develop his Catholic fantasy novels and has clearly made a big impact in France. These books, as one reviewer on amazon.fr puts it, are "mieux qu'Harry Potter". And the first volume is also now available as a graphic novel. Let's hope for an English translation before too long.

But what about St Therese? Let's just say that Michael Dor is not the author's real name and that you can discover more about his background from this site.

Monday, 1 October 2012

An Unusual Patron Saint of Lost Causes

A few days ago it was the Hail Mary pass, now it's "Seve Ballesteros, the patron saint of lost causes". At least that's what Iain Carter, the BBC's Golf Correspondent reckons.

So what's going on here? Sport seems to be bringing out the religious (or pseudo-religious) in people this year in all sorts of different ways. I suspect calling Seve the patron saint of lost causes is just a throwaway comment but it's tempting to see it as something more: a residual belief in the efficacy of praying to saints or, even more interestingly, a new influence to Britain coming from Catholic countries like Spain.

And it's not just golf. Now that so many footballers cross themselves when coming onto the pitch it's almost as if Henry VIII never broke with England's thousand-year Catholic past. Almost.

So what's going on here? Sport seems to be bringing out the religious (or pseudo-religious) in people this year in all sorts of different ways. I suspect calling Seve the patron saint of lost causes is just a throwaway comment but it's tempting to see it as something more: a residual belief in the efficacy of praying to saints or, even more interestingly, a new influence to Britain coming from Catholic countries like Spain.

And it's not just golf. Now that so many footballers cross themselves when coming onto the pitch it's almost as if Henry VIII never broke with England's thousand-year Catholic past. Almost.

Saturday, 29 September 2012

The Hail Mary Pass

The BBC (online) Magazine has had some really interesting English Language articles recently, including this one on 'Britishisms and the Britishisation of American English'.

However, it wasn't until I read this article on 'The shared language of politics and sport' that I came across the Hail Mary pass, which probably says more about my British parochialism than about the prevalence of the term. For fellow Brits, a Hail Mary pass is a long forward pass made in the closing stages of an American Football game. Chuck it - say a Hail Mary - hope someone catches it in the end zone. That's the basic idea.

"Stepping up to the plate" has become something of a cliche in British political discourse. Somehow I can't see the Hail Mary pass catching on in the same way.

Sunday, 23 September 2012

Hobbitus Ille

Fr Tim Finigan has a welcome reminder of the lure of The Hobbit on his blog today. He also

provides a useful link to this tremendously interesting page from the New

Liturgical Movement on Tolkien’s liturgical views.

However, what made me chuckle was the link in the Com Box to

the new Latin translation of The Hobbit and,

especially, the learned discussion of the finer points of translation in the

Amazon reviews.

It reminded me of one of my tutors at university. A learned

but rather eccentric man, he gave his young son Asterix books to read. This

rather surprised us until we heard that it was Asterix translated into Latin.

Sunday, 16 September 2012

Chinese Catholic Literature Then and Now

There have been - and still are - some wonderful Chinese Catholic authors. One of the best known of these writers is Wu Li, who was not only one of the orthodox masters of early Qing-dynasty painting but also a poet and Jesuit priest.

The most comprehensive guide to Wu Li can be found here (with further details here) but a more accessible introduction to his work can be found here. According to Chaves, his poetic sequence "'Singing of the Source and Course of Holy Church' succeeds in achieving Wu Li's goal of creating a Chinese Christian poetry, true to Chinese traditions of allusion, parallelism, and other familiar poetic techniques and true also to orthodox Christian theology, piety, and liturgical solemnity." Rather than do him the injustice of a brief quotation, I'll try to return to some of the poems themselves (in Chinese and in English translation) in a later post.

Another great Chinese Catholic writer who is only now beginning to be given her due is Su Xuelin. This article from Harvard's Divinity School is encouraging, though also a little baffling. Although Su Xuelin converted to Catholicism in the 1920s while studying in France, Zhange Ni argues that the religion her alter-ego embraces in Ji Xin, the novel Su Xuelin wrote about her conversion, "is not Catholicism or Western religion per se, but a not-so-readily-available, still-struggling-into-being Chinese discourse of religion, which cannot be reduced to a slavish adoption of modern Western concepts of religion."

But what about today? I've written before about Fan Wen and the good news is that the first volume of his 水乳大地 trilogy is due to be published in French translation in January 2013. Maybe an English translation will follow?

Thursday, 6 September 2012

Lourdes and Literature

I have just come back from Lourdes where I eventually got round to reading Ruth Harris's fascinating Lourdes: Body and Spirit in the Secular Age. Harris is a historian at Oxford University and an exceptionally fair-minded historian. Coming from a Jewish secularist background, she went on a pilgrimage to Lourdes while writing this book and is clearly a sympathetic outsider.

Just occasionally her secularism struggles in the face of the miracles of Lourdes but, for the most part, she writes with an impressive open-mindedness and objectivity. Take this sentence, for example: "Of all the many marvels that Lourdes produced, de Rudder's cure shows the limits of historical explanation: while so many other healings could be the result of misdiagnosis - even in the apparently 'certain' realm of cancer, tuberculosis or paralysis - the case of de Rudder dismays and perplexes." (344-5)

The lack of a direct object is fascinating. Does she mean it dismays and perplexes her? Or historians? Or secularists? The intransitive use of transitive verbs perhaps only draws attention to the limits of the historical method.

But that's slightly by the by.

One reason I enjoyed the book was because Harris writes so well about Emile Zola and Lourdes. It is rather ironic that two of the most well-known novels about Lourdes were written by non-Catholics: Zola's anti-clerical and anti-Catholic Lourdes and Franz Werfel's much more sympathetic The Song of Bernadette (which was written to fulfil the vow the author made when he found shelter in the town while fleeing the Nazis during World War II).

According to Harris, "Zola's journal shows how his journey [to Lourdes] produced in him powerful emotions and an intense ambivalence, feelings that he would repress once he returned to the familiar philosophical, literary and political world of the capital. The resulting book returned to the terrain of literary naturalism, and many of the ambiguities of his experience were stripped away."

Most disturbing of all was his rewriting of history. As Harris again points out, "his reworking of the case of Marie Lebranchu was palpably untrue: she never did relapse [as described in Zola's novel] and remained the living embodiment for Catholics of his bad faith."

So where do we look for less jaundiced novelistic descriptions of Lourdes?

So where do we look for less jaundiced novelistic descriptions of Lourdes?

Brian Sudlow - who is a very interesting academic - has a short section on Lourdes in his Catholic literature and secularisation in France and England, 1880-1914. He mentions, among other mainly non-fiction accounts, Emile Baumann's L'Immolé in which one of the characters "prays in vain for a miracle to cure her invalidity, and obtains it only later in the novel through the miraculous waters of Lourdes."

I also came across the much more recent, but still untranslated, work of Bernadette Pécassou-Camebrac while in Lourdes. Both La Belle Chocolatière and Le Bel Italien look as though they would be well worth reading.

I also came across the much more recent, but still untranslated, work of Bernadette Pécassou-Camebrac while in Lourdes. Both La Belle Chocolatière and Le Bel Italien look as though they would be well worth reading.

Monday, 27 August 2012

Emily Hickey

Just over a year ago - I'm slow on the uptake - Carol Rumens chose 'The Ship from Tirnanoge' by Emily Hickey as her poem of the week in The Guardian. Like Rumens, I'd not heard of Hickey before but she sounds quite a fascinating figure: "A talented and complex writer, scholar and translator, Emily Henrietta Hickey, 1845-1923, was the daughter of a Protestant rector of Goresbridge, County Wexford. She eventually become a lecturer at Cambridge University, and a Catholic convert."

Rumens also recommends Hickey's Our Catholic Heritage in English Literature of Pre-Conquest Days which begins like this:

"This little book makes no claim to be a history of pre-Conquest Literature. It is an attempt to increase the interest which Catholics may well feel in this part of the great 'inheritance of their fathers.' It is not meant to be a formal course of reading, but a sort of talk, as it were, about beautiful things said and sung in old days: things which to have learned to love is to have incurred a great and living debt."

Sunday, 19 August 2012

Catholic Sci-fi

It's an interesting story not just because it contains a short account of a mass on Mars but also because it depicts the quasi-redemptive nature of labour in the harsh Martian environment. However, although it's worth reading, I can't honestly say that it's anything more than interesting. The problem with sci-fi is that it dates so quickly; this particular story is ultimately unconvincing largely because science and technology moved on so much more quickly than Miller envisaged they would in 1953.

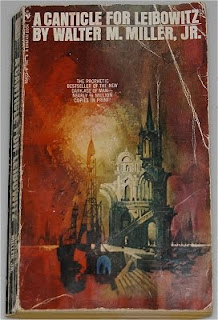

A better bet is Miller's best-known work, A Canticle for Leibowitz, which I remember being (surprisingly) very popular in evangelical circles during my student years. Miller wrote the book after being involved in bombing raids on the great Benedictine abbey at Monte Cassino during World War II. His own relationship with the Church - and, indeed, his own life - was complicated but this is one science-fiction novel that has stood the test of time. (Though see this interesting comparison with Cormac McCarthy's The Road.)

I'm not a great sci-fi expert so I can't write with great assurance but Gene Wolfe (who is a great fan of G. K. Chesterton) is often held out as the greatest Catholic writer of science fiction. His The Book of the New Sun is recommended in particular.

There's also an interview with Sandra Miesel at Ignatius Insight here which provides a list of other authors worth looking out for.

Sunday, 12 August 2012

More on Tolkien in Love

BBC Radio recently broadcast a programme about Tolkien in Love but I suspect Tolkien was actually more interested in love than in being in love.

One of his most interesting letters (No 43 in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien to his son Michael from March 1941) deals with love, marriage and his relationship with Edith, his wife. I could happily quote chunk after chunk of it but I'll restrict myself to two powerful passages. I have add one paragraph break for the sake of clarity in the limited space available here:

"The essence of a fallen world is that the best cannot be attained by free enjoyment, or by what is called ‘self-realization’ (usually a nice name for self-indulgence, wholly inimical to the realization of other selves); but by denial, by suffering. Faithfulness in Christian marriage entails that: great mortification. For a Christian man there is no escape. Marriage may help to sanctify & direct to its proper object his sexual desires; its grace may help him in the struggle; but the struggle remains. It will not satisfy him – as hunger may be kept off by regular meals. It will offer as many difficulties to the purity proper to that state, as it provides easements. No man, however truly he loved his betrothed and bride as a young man, has lived faithful to her as a wife in mind and body without deliberate conscious exercise of the will, without self-denial. Too few are told that – even those brought up ‘in the Church’. Those outside seem seldom to have heard it. One of his most interesting letters (No 43 in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien to his son Michael from March 1941) deals with love, marriage and his relationship with Edith, his wife. I could happily quote chunk after chunk of it but I'll restrict myself to two powerful passages. I have add one paragraph break for the sake of clarity in the limited space available here:

"When the glamour wears off, or merely works a bit thin, they think they have made a mistake, and that the real soul-mate is still to find. The real soul-mate too often proves to be the next sexually attractive person that comes along. Someone whom they might indeed very profitably have married, if only -. Hence divorce, to provide the ‘if only’. And of course they are as a rule quite right: they did make a mistake. Only a very wise man at the end of his life could make a sound judgement concerning whom, amongst the total possible chances, he ought most profitably to have married! Nearly all marriages, even happy ones, are mistakes: in the sense that almost certainly (in a more perfect world, or even with a little more care in this very imperfect one) both partners might have found more suitable mates. But the ‘real soul-mate’ is the one you are actually married to."

The letter ends - or at least the extract we are given by Humphrey Carpenter ends - with this amazing passage:

"Out of the darkness of my life, so much frustrated, I put before you the one great thing to love on earth: the Blessed Sacrament….. There you will find romance, glory, honour, fidelity, and the true way of all you loves upon earth, and more than that: Death: by the divine paradox, that which ends life, and demands the surrender of all, and yet by the taste (or foretaste) of which alone can what you seek in your earthly relationships (love, faithfulness, joy) be maintained, or take on that complexion of reality, of eternal endurance, which every man’s heart desires."

Tuesday, 7 August 2012

James MacMillan - a world premiere and a fascinating discussion

James MacMillan's Credo is receiving its World Premiere at the Proms this evening. During the interview MacMillan will discuss Religion in Music with Louise Fryer and the Director of Music at St Paul's Cathedral.

MacMillan is quite an inspirational figure. Speaking on Radio 3 this morning, he was quite happy to refer to himself as a Catholic composer, which may not seem surprising until you think about how many people are happy to call themselves Catholic authors.

As I have suggested elsewhere, Catholic writers have something to learn from the example of Catholic composers like him.

As I have suggested elsewhere, Catholic writers have something to learn from the example of Catholic composers like him.

Sunday, 5 August 2012

Tolkien in Love

Tolkien rightly distrusted all attempts to find links between authors' biographies and their books, not because such links don't exist but because of their complexity:

"An author cannot of course remain wholly unaffected by his experience, but the ways in which a story-germ uses the soil of experience are extremely complex, and attempts to define the process are at best guesses from evidence that i inadequate and ambiguous." (from the Foreward to The Lord of the Rings)

With that proviso, I'd like to draw attention to this programme from BBC Radio 4:

Novelist Helen Cross, who herself lives in Birmingham, uncovers the story of the young J.R.R. Tolkien, falling in love with Edith Bratt. The love story of Beren and Luthien at the heart of his novel The Silmarillion was inspired by their relationship. They were both orphans, living in a boarding house in Edgbaston, Birmingham. The teenagers would talk out of their respective bedroom windows until dawn, and go for cycle rides to the Lickey Hills. However, when their romance was discovered, Tolkien's guardian, Father Francis Morgan, forbade Tolkien to see Edith until he came of age.Tolkien won an Exhibition to Oxford and Edith went to live in Cheltenham. But at midnight, as he turned 21, Tolkien wrote to Edith saying his feelings were unchanged. Unfortunately, in the intervening years, Edith had got engaged to someone else. Tolkien got on a train and she met him at Cheltenham station. They walked out to the nearby countryside and Tolkien persuaded her to break off her engagement and marry him instead. But the First World War was about to intervene, and Tolkien volunteered and was sent to the Somme.

Helen Cross visits key locations in Birmingham, Cheltenham and Oxford, to tell the story of Tolkien's young life and the love story at the heart of it.

Readings by David Warner as Tolkien and Ed Sear as the young Tolkien.

I'd want to point out that The Silmarillion is clearly not a novel but, nonetheless, it's always worth hearing more about Tolkien and this programme is available online only for five more days.

Friday, 3 August 2012

Articles now available online

The Catholic Herald archive is now available free and online which means that all sorts of interesting articles and reviews are available without a subscription. It also means that three of my articles are now easier to access.

Click here for my review of Amy Hungerford's Postmodern Belief: American Literature and Religion Since 1960.

Click here for my article on the Chinese Prime Minister who became a Catholic Monk and Priest.

Click here for my article on adoption. (Not strictly relevant, I realise, but there you go).

Tuesday, 24 July 2012

What Happened to Sophie Wilder

However, having read about it on the ever-informative Image Update and seen that it received a favourable review from the New York Times and rave reviews from readers at Amazon, I became more intrigued, so I'm putting the information out there.

Wednesday, 18 July 2012

Frank Cottrell Boyce on "the great Catholic artist"

"Hitchcock is the great Catholic artist, returning again and again to the themes of the fallen nature of creation. Sometimes – The Wrong Man,The Birds – this comes out as a bleakly thrilling feeling that everyone is guilty. In Notorious, however (and in Shadow of a Doubt, Psycho, North by Northwest and Vertigo), it plays the opposite way – that the world is fallen and therefore the best are only different from the worst by the grace of God; that our worst failings are forgivable and repairable; and that no matter how compromised we are, we can – and must – love one another. It's the reason his great thrillers are also great love stories. It's the source of the power of that last shot – a hungover pietà – of Grant carrying Bergman out of the house of shadows and into the possibility of love."

Perhaps that's a question for some future exam paper: "Hitchcock is the great Catholic artist. Discuss."

Saturday, 14 July 2012

The Tour de France, World War II and an Italian, Catholic Schindler

Road to Valor, which has just been published, looks absolutely fascinating. Here's how the publishers describe it:

Road to Valor is the inspiring, against-the-odds story of Gino Bartali, the cyclist who made the greatest comeback in Tour de France history and secretly aided the Italian resistance during World War II.

Gino Bartali is best known as an Italian cycling legend: the man who not only won the Tour de France twice, but also holds the record for the longest time span between victories. During the ten years that separated his hard-won triumphs, his actions, both on and off the racecourse, ensured him a permanent place in Italian hearts and minds.

In Road to Valor, Aili and Andres McConnon chronicle Bartali’s journey, starting in impoverished rural Tuscany where a scrawny, mischievous boy painstakingly saves his money to buy a bicycle and before long, is racking up wins throughout the country. At the age of 24, he stuns the world by winning the Tour de France and becomes an international sports icon.

But Mussolini’s Fascists try to hijack his victory for propaganda purposes, derailing Bartali’s career, and as the Nazis occupy Italy, Bartali undertakes secret and dangerous activities to help those being targeted. He shelters a family of Jews in an apartment he financed with his cycling winnings and is able to smuggle counterfeit identity documents hidden in his bicycle past Fascist and Nazi checkpoints because the soldiers recognize him as a national hero in training.

After the grueling wartime years, Bartali fights to rebuild his career as Italy emerges from the rubble. In 1948, the stakes are raised when midway through the Tour de France, an assassination attempt in Rome sparks nationwide political protests and riots. Despite numerous setbacks and a legendary snowstorm in the Alps, the chain-smoking, Chianti-loving, 34-year-old underdog comes back and wins the most difficult endurance competition on earth. Bartali’s inspiring performance helps unite his fractured homeland and restore pride and spirit to a country still reeling from war and despair.

Set in Italy and France against the turbulent backdrop of an unforgiving sport and threatening politics, Road to Valor is the breathtaking account of one man’s unsung heroism and his resilience in the face of adversity. Based on nearly ten years of research in Italy, France, and Israel, including interviews with Bartali’s family, former teammates, a Holocaust survivor Bartali saved, and many others, Road to Valor is the first book ever written about Bartali in English and the only book written in any language to fully explore the scope of Bartali’s wartime work. An epic tale of courage, comeback, and redemption, it is the untold story of one of the greatest athletes of the twentieth century.

It's also worth pointing out that Bartali was driven by his strong Catholic faith and that when he delivered messages that had been hidden in his bicycle frame he was delivering them to a network of Catholic priests who were helping Jews to escape from the Nazis. Which is not a side of World War II we hear enough about.

Tuesday, 10 July 2012

World War II and Children's Literature

It’s a fair bet that any Key Stage 3 (11-14 year old) students who are studying World War II will have come across either John Boyne’s The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas or Morris Gleitzman’s trilogy: Once, Then and Now. One of the most striking features of these books is the narrative technique. Though Boyne uses a third-person narrator in The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, the focaliser (for all but the last section) is Bruno, the 9-year-old son of the Auschwitz commandant. Gleitzman’s novels are narrated by Felix who, at ten years old, is even more clueless than Bruno, at least at first. As Leo Benedictus has pointed out in an excellent article about hindered narrators, “this kind of novel, told in the first person by a character with a limited ability to understand the world or write about it, is the genre that defines our times”.

So what's going on here? Using a hindered narrator often helps an author create a sense of complicity between the writer and the reader. We are encouraged to read between the lines, to bring our contextual knowledge to bear on the book, to judge the narrator. However, with children it's not so straightforward. They may or may not have contextual knowledge. They may not be able to stand back so easily (depending on their age, quite apart from anything else).

It would, in other words, be easy to see The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas and Once, Then and Now as fundamentally different from earlier children's fiction, from, say, The Silver Sword or Hilda van Stockum's The Winged Watchman. The authors are more knowing and the readers are expected to be so as well. But it may not be quite as simple as this.

Like The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, The Winged Watchman, a novel about the Dutch Resistance, is written in the third person but gives us a child’s perspective. It differs not in kind but in degree. The setting, and many of the characters, are openly Catholic but, more significant, is the subject matter. Rather than dealing directly with the holocaust, van Stockum focusses on resistance to the Nazis and so has to have write differently.

What has changed since her time is that children's literature has increasingly addressed the toughest of subjects head on, including the holocaust. It is therefore no surprise that children's authors like Boyne and Gleitzman use hindered narrators. How else could they possibly present such horrifying events to their young readers?

However, we shouldn't be fooled into thinking that the horrors of war have never been addressed in children's fiction before. It's just that in books like The Silver Sword and The Winged Watchman, both of which also focus on the experience of children in the war, the holocaust is held at arm's length.

Does this make them less valid? More escapist? I don't think so. Hilda van Stockum's response to the horrors of the war is no less historically informed and certainly no less valid in its own way than Boyne’s or Gleitzman’s. Boyne and Gleitzman gained something from having the benefits of historical distance but van Stockum gained something from living when she did and from having relatives who experienced life in the Netherlands during the war.

I haven't got space to deal fully with Boyne’s and Gleitzman’s books but I'll try to return to them another time. Gleitzman’s books, in particular, deal explicitly with Catholicism in interesting but challenging ways and so deserve further consideration.

Boyne's and Gleitzman's novels are certainly worth reading with care but we shouldn't neglect earlier fiction about the war, so if you want to read some more of van Stockum's wonderful children’s fiction you could click here.

Thursday, 5 July 2012

A Sonnet for St Thomas the Apostle

Click here for a sonnet on St Thomas the Apostle by the interesting Anglican poet, priest, academic and musician Malcolm Guite.

I also quite like this villanelle on the purpose of poetry.

And, finally, you can also download the opening chapter of his Faith, Hope and Poetry: Theology and the Poetic Imagination by clicking here.

I also quite like this villanelle on the purpose of poetry.

And, finally, you can also download the opening chapter of his Faith, Hope and Poetry: Theology and the Poetic Imagination by clicking here.

Sunday, 1 July 2012

Pictures in the Cave

The stories are not explicitly Catholic tales but there are a few intriguing moments. The first comes when Robert the Bruce seeks refuge in a monastery:

"You understand," said the abbot, "we don't ask here whether a man is a king or a beggar. It's sufficient that he is an immortal soul. The Kingdom of Heaven is of more concern to us than Scotland or England or Norway. This much I grant - a man can work and pray better if he is a free man in a free country."

The second is the wonderful 'The Feast of the Strangers', an Orkney Fable as he called it, which retells the Christmas story with a powerfully Orcadian setting.

And the third is the end of the book when all the characters seem to meet again in the afterlife. Like Muriel Spark, another great Scottish Catholic writer, George Mackay Brown was fascinated by time - God's time, our time, eternity, and the pull of free will, predestination and determinism. His Booker-shortlisted Beside the Ocean of Time famously slips in and out of different historical eras, for example. Some of his novels are coming back into print. Let's hope his children's books follow.

Friday, 22 June 2012

Dana Gioia's poetry

You can read some of Gioia's poems, essays and reviews on his website but I'd like to draw attention to a couple of poems from his most recent collection Pity the Beautiful that might work well in the classroom: 'Majority' and 'Pity the Beautiful' itself.

His lecture on 'The Catholic Writer Today' also sounds fascinating, though I can't find a copy of the text or a recording of the lecture itself. The lecture is summarised here and here.

Sunday, 17 June 2012

The Curse of the Darkling Mill

Despite the success of the film of the novel, the book is still very difficult to obtain in English, which is a real shame because it is both “an eerie tale of sorcery and nightmares” (as the publishers describe it) and a deeply Catholic work.

The novel is given an explicit Christian context from the very first pages when Krabat and two friends, dressed as the Three Kings, are begging during the Christmas season.

However, it is Krabat’s pride, his rejection of the other magi, which, at least in part, brings about his downfall. By breaking the highly symbolic group of three beggar boys and striking off on his own, he places himself in the power of an evil miller and becomes one of his twelve dark apprentices. Quite what he has let himself in for only becomes apparent later in the novel when he discovers that the mill is grinding not wheat but human bones.

Krabat is an assertion of the importance of the Wendish culture and language in modern day Germany as well as a Christian fable, but it is also a meditation on Hitler’s rise to power and the horrors of the holocaust. Krabat becomes, if not one of Hitler’s willing executioners, then at least an accomplice as he is seduced by the mill’s material comforts into ignoring the evidence of evil around him.

After a while the evidence becomes too hard to ignore completely: each New Year one of the apprentices is murdered and replaced but by then Krabat is in too deeply to be able to escape. When his friend, Tonda, is murdered Krabat tries to say the Lord’s Prayer over his grave, “but somehow it had slipped his memory; he began it again and again, but he could never get to the end of it”.

Drawn deeper and deeper into the mill’s satanic rites, Krabat’s only link with the outside world comes each Easter when he hears the voice of a young girl singing as part of the village’s Easter procession. Ultimately, it is this young girl and the power of love which overcomes the darkness but to write more would be to spoil the plot even more than I have done already.

This is a book which packs a punch: Preussler, one of Germany’s best-loved children’s authors, writes about both the banality and the lure of evil. However, in a world where few topics now seem to be off-limits for children’s fiction, we should not be concerned about a book which deals with such topics from a Christian perspective and without preaching. The Curse of the Darkling Mill deserves to be more widely read.

Thursday, 14 June 2012

Willa Cather's 'My Antonia'

Friday, 8 June 2012

Ernest Hemingway, Cormac McCarthy and 'The Road'

It is perilous to attempt to analyse too specifically what any author gains from those who have gone before but I can't help but wonder whether light cannot be shed on the final enigmatic paragraph in Cormac McCarthy's The Road through reading one of Hemingway's fine short stories. [Incidentally, for more on (what I've written about) Hemingway click here and here.]

Many have commented on The Road's unexpected ending:

"Once there were brook trout in the streams in the mountains. You could see them standing in the amber current where the white edges of their fins wimpled softly in the flow. They smelled of moss in your hand. Polished and muscular and torsional. On their backs were vermiculate patterns that were maps of the world in its becoming. Maps and mazes. Of a thing which could not be put back. Not be made right again. In the deep glens where they lived all things were older than man and they hummed of mystery."

But few have compared it with the opening of Hemingway's 'Big Two-Hearted River' which also deals with a dead landscape and trout that live on in the streams:

"The train went on up the track out of sight, around one of the hills of burnt timber. Nick sat down on the bundle of canvas and bedding the baggage man has pitched out of the door of the baggage car. There was no town, nothing but the rails and the burned-over country. The thirteen saloons that has lined the one street of Seney had not left a trace. The foundations of the Mansion House hotel stuck up above the ground. The stone was chipped and split by the fire. It was all that was left of the town of Seney. Even the surface had been burned off the ground."

So far so apocalyptic, one might think. But the story continues:

"Nick looked at the burned-over stretch of hillside, where he had expected to find the scattered houses of the town and then walked down the railroad track to the bridge over the river. The river was there. It swirled against the log piles of the bridge. Nick looked down into the clear, brown water, coloured from the pebbly bottom, and watched the trout keeping themselves steady in the current with wavering fins. As he watched them they changed their positions by quick angles, only to hold steady in the fast water again. Nick watched them a long time."

There are plenty of differences between the two stories, of course. Nick is a solitary character whereas The Road is a novel about relationships; Hemingway's trout survive the fire storm: McCarthy's are only a memory. But I don't think it's too fanciful to see in McCarthy's novel a trace of the Hemingway story.

So what reason could there be for this literary recollection? One possibility, I think, can be found a few paragraphs on in Hemingway's story. "Seney was burned," the narrator tells us, "the country was burned over and changed, but it did not matter. It could not all be burned."

As I've argued before, The Road is a strangely hopeful novel but it is an open-ended one. Does the boy survive? Is the destruction total? What the final paragraph in its literary context may suggest is that the answers to those two questions are 'Yes' and 'No'. There is a place where the fire has not burned. Survival is possible. And with survival may come love, the deep mystery that hums at the heart of this great novel.

Wednesday, 6 June 2012

Some Scottish Catholic Literature

There is some really interesting work going on in Scotland at the moment. Juliet Linden Bicket, for example, submitted her PhD thesis this year on A 'God-ordained web of creation': the faithful fictions of George Mackay Brown.

Here's the abstract:

"This thesis represents the first extensive examination of the ‘faithful fictions’ of the Orkney writer George Mackay Brown (1921-1996). Until now, critical appreciations of the Catholic imagination informing Brown’s opus have been vague and Brown has been seen as a throwback; his Catholicism only part of a reactionary impulse that denies modernity a place in his oeuvre. Through a thematic critical analysis of four major strands of Brown’s corpus that display his Catholic imagination, it is contended that Brown has been misunderstood by the Scottish literary-critical tradition, and that his creative work on religious subjects is diverse, experimental and devotional. The thesis provides a biography of Brown’s faith. It looks at his conversion accounts, and it discusses the interaction between these and other accounts of (spiritual) autobiography. The thesis looks in a detailed way at three mediators of grace in Brown’s faithful fictions: the Virgin Mary, St Magnus, and Christ, whose nativity Brown frequently depicts. By discussing their different roles, depictions and the various literary forms that tell their stories, this study will discover the ways in which Brown encapsulates his Catholic faith in his creative work.

"The thesis questions whether Catholicism harms his literary output, as some critics have suggested, and shows the ways in which Brown’s writing interacts with other Catholic literature – old and new, at home and abroad. Manuscripts, including several unpublished poems, plays and stories, will be referenced throughout, as will rare and unseen correspondence. The thesis takes in the entire scope of Brown’s body of work and is not limited to a single mode or genre in his corpus. Ultimately, this study contends that Brown is an excellent case-study of the neglected Catholic writer in twentieth-century Scotland, and that there is much work to be done in appraising the Catholic imaginations of many post-Reformation Scottish Catholic writers."

So let's have a look at some of these neglected Catholic writers. I've blogged here and here about Muriel Spark and there's a huge amount to say about George Mackay Brown himself, including what Juliet Linden Bicket writes here.

We could also mention Bruce Marshall, Compton Mackenzie and others, but I want to draw attention to someone who is virtually unknown south of the border: Fionn Mac Colla, some of whose work can be found here. There is much in his work to challenge any English speaker but it's clearly a challenge worth facing.

As Juliet Linden Bicket rightly points out, "there is much work to be done in appraising the Catholic imaginations of many post-Reformation Scottish Catholic writers." Let's hope that her work is just the beginning of this reappraisal.

As Juliet Linden Bicket rightly points out, "there is much work to be done in appraising the Catholic imaginations of many post-Reformation Scottish Catholic writers." Let's hope that her work is just the beginning of this reappraisal.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)