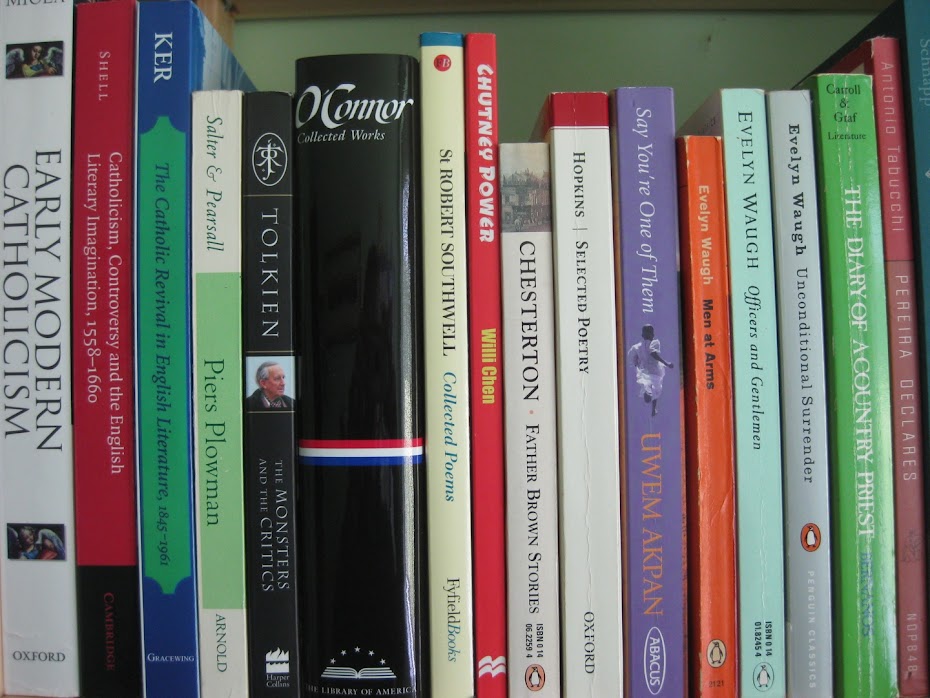

As I mentioned in a previous post, the poetry of St Robert Southwell is beginning to receive the attention it deserves. Here is his wonderful poem on the Nativity of Christ:

Behold the father is his daughter's son,

The bird that built the nest is hatch'd therein,

The old of years an hour hath not outrun,

Eternal life to live doth now begin,

The word is dumb, the mirth of heaven doth weep,

Might feeble is, and force doth faintly creep.

O dying souls! behold your living spring!

O dazzled eyes! behold your sun of grace!

Dull ears attend what word this word doth bring!

Up, heavy hearts, with joy your joy embrace!

From death, from dark, from deafness, from despairs,

This life, this light, this word, this joy repairs.

Gift better than Himself God doth not know,

Gift better than his God no man can see;

This gift doth here the giver given bestow,

Gift to this gift let each receiver be:

God is my gift, Himself He freely gave me,

God's gift am I, and none but God shall have me.

Man alter'd was by sin from man to beast;

Beast's food is hay, hay is all mortal flesh;

Now God is flesh, and lies in manger press'd,

As hay the brutest sinner to refresh:

Oh happy field wherein this fodder grew,

Whose taste doth us from beasts to men renew!

The bird that built the nest is hatch'd therein,

The old of years an hour hath not outrun,

Eternal life to live doth now begin,

The word is dumb, the mirth of heaven doth weep,

Might feeble is, and force doth faintly creep.

O dying souls! behold your living spring!

O dazzled eyes! behold your sun of grace!

Dull ears attend what word this word doth bring!

Up, heavy hearts, with joy your joy embrace!

From death, from dark, from deafness, from despairs,

This life, this light, this word, this joy repairs.

Gift better than Himself God doth not know,

Gift better than his God no man can see;

This gift doth here the giver given bestow,

Gift to this gift let each receiver be:

God is my gift, Himself He freely gave me,

God's gift am I, and none but God shall have me.

Man alter'd was by sin from man to beast;

Beast's food is hay, hay is all mortal flesh;

Now God is flesh, and lies in manger press'd,

As hay the brutest sinner to refresh:

Oh happy field wherein this fodder grew,

Whose taste doth us from beasts to men renew!

Or, to be more accurate, that was his poem with spelling and punctuation updated. More lingusitically interesting and almost equally comprehensible is what he actually wrote:

Behoulde the father is his daughters sonne

The bird that built the nest, is hatchd therein

The old of yeres an hower hath not outrunne

Eternall life to live doth nowe beginn

The worde is dumm the mirth of heaven doth weepe

Mighte feeble is and force doth fayntly creepe

O dyinge soules behould your living springe

O dazeled eyes behould your sunne of grace

Dull eares attend what word this word doth bringe

Up heavy hartes with joye your joy embrace

From death from darke from deaphnesse from despayres

This life this light this word this joy repaires

Gift better then himself god doth not knowe

Gift better then his god no man can see

This gift doth here the giver given bestowe

Gift to this gift lett ech receiver bee

God is my gift, himself he freely gave me

Gods gift am I and none but God shall have me.

Man altered was by synn from man to best

Bestes foode is haye haye is all mortall fleshe

Now god is fleshe and lyves in maunger prest

As haye the brutest synner to refreshe.

O happy feilde wherein this foder grewe

Whose taste doth us from beastes to men renewe.