Here's my review of Amy Hungerford's Postmodern Belief: American Literature and Religion since 1960 (Princeton University Press, 2010), which appeared in last week's Catholic Herald:

It is often assumed, in this country at least, that the age of great Christian literature is over. What we have instead, the argument goes, are books which either ignore religion completely, mock it mercilessly, or treat it as an irrational threat.

It is also assumed that the situation is quite different in the US where affirmations of religious belief are all but obligatory for politicians and where highly respected authors such as John Updike have espoused religious belief.

However, as Amy Hungerford demonstrates in Postmodern Belief, religious assumptions are also often underarticulated in contemporary American literature and in secular academic discourse.

What Hungerford, who is professor of English at Yale University, attempts to do in her fascinating book is to bring these basic assumptions out into the open in order to examine just how literature and religion have intersected over the last 50 years.

Her book is not, as the rather misleading title suggests, a study of postmodernism. Indeed, part of her purpose in writing is to move beyond postmodern interpretations of religion and literature. Nor is it a comprehensive survey. Hungerford is quite open about the fact that she omits as much as she includes.

Nonetheless, Hungerford still deals with an impressive range of writers, from Salinger and Ginsberg to Cormac McCarthy and Toni Morrison and what she has to say about them is incisive and often original.

As the list of authors above suggests, she writes mainly about novelists who have emerged from within the Judaeo-Christian tradition. Indeed, the absence of any discussion of Islam is one the book's most surprising features, not least because of 9/11's continuing reverberations in American literature.

Of most interest to readers of The Catholic Herald will probably be her chapter on what she calls, after Don DeLillo, "The Latin Mass of Language" in which she argues convincingly that "DeLillo ultimately transfers a version of mysticism from the Catholic context into the literary one, and that he does so through the model of the Latin mass."

With a good many qualifications, Hungerford argues that DeLillo is a "religious writer" by paying particular attention to what is often regarded as his masterpiece, Underworld.

Clearly DeLillo is not a religious writer in any traditional sense of the term but, in Hungerford's view, the way his use of language becomes infused with religious meaning derives, at least in part, from his Catholic upbringing.

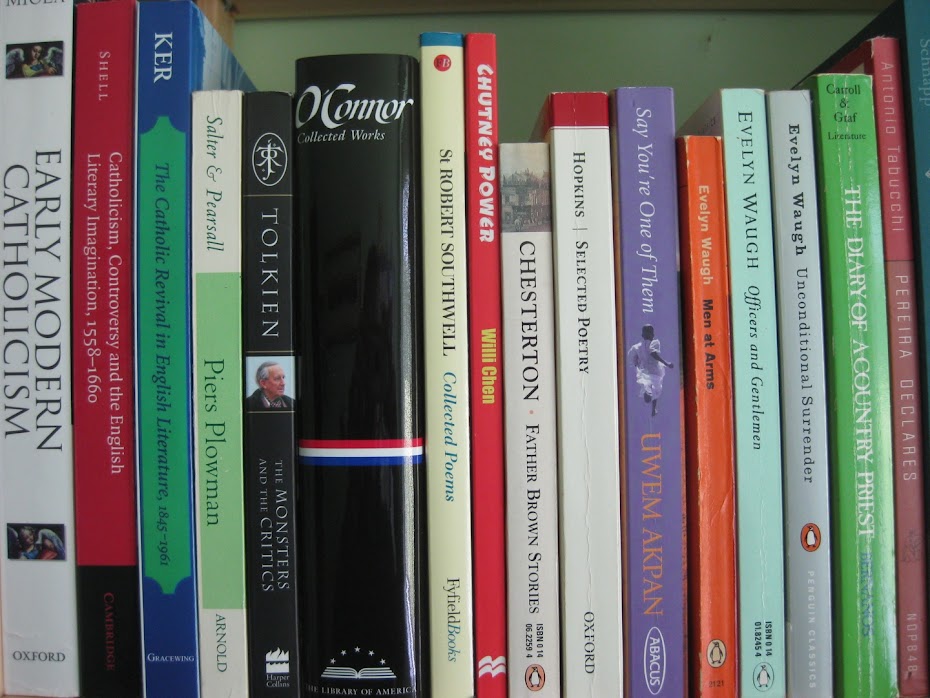

Indeed, Catholics may be heartened to discover that "one of the surprising findings of this book ... is the importance of the Roman Catholic religious imagination in the literature of the period, even - or rather, especially, outside the body of 'Catholic novels' by believers such as Flannery O'Connor, Katherine Anne Porter, Walker Percy, or Graham Greene."

Hungerford seeks to overturn common assumptions about post-Protestant secularity by drawing attention not only to the Catholic backgrounds of J.D. Salinger, Cormac McCarthy, Toni Morrison and others but also to the presence of many Catholic writers and critics in the New Critical movement and in the Creative Writing Programs which derived their modus operandi from it.

However, there are limits to the satisfaction Catholics might feel about these reinterpretations. In the very first sentence of the book, for example, Hungerford declares that "this book is about belief and meaninglessness, and what it might mean to believe in meaninglessness."

Her central argument is that, as belief has been emptied of doctrinal content, not just former Catholics like DeLillo but American authors in general have invested language itself with religious meaning. Although she does write, extremely interestingly, about Marilynne Robinson, for example, Hungerford is not primarily interested in the work of believers.

She is a highly sympathetic critic but she is ultimately more concerned, as she explains in a personal conclusion, with the question of how we can "be post-religious and still have literature worth venerating".

Much of the literature she discusses, therefore, is post-Christian and most of the authors she writes about have only the most tangential of links to the Catholic church, being, for the most part, either indifferent or lapsed.

However, it is arguable that by writing about practising Catholic authors only in passing, Hungerford leaves some fundamental questions about the relationship of literature and religion in America unaddressed, let alone unanswered.

By beginning her analysis in 1960, on the eve of the Second Vatican Council, she also effectively concedes the case for a hermeneutic of discontinuity and so perhaps fails to give full credit to the ongoing influence of orthodox believers such as Flannery O'Connor and orthodox beliefs in the post-conciliar literary world.

Nevertheless, it is easy to indulge in wishful thinking. Clearly Vatican II, or at least contemporary interpretations of Vatican II, was a cataclysmic event not only in the Church but also in literary America and authors like DeLillo were deeply affected by it.

What Hungerford doesn't touch upon, and what, to be fair, may only become clear over the course of the next decade or more, is what difference the re-evaluation of Vatican II associated most strongly with Joseph Ratzinger both before and after he became pope will transform American (and other) attitudes to literature and the arts.

Much as I enjoyed Postmodern Belief, the book which deals with those questions is one I am really looking forward to reading.