Cruickshank, who was Professor of French at the University of Sussex, argued that François Mauriac, Georges Bernanos, and Julien Green "all managed to command a wide readership while producing a considerable body of work in which they have written consciously as Catholics." Even if they hadn't influenced various English writers (Graham Greene most notably) they would still be of considerable interest in their own right.

The "avoidance of naive religious didacticism, notable in Mauriac' best work as well as in the novels of Bernanos and Green, goes some way towards explaining the considerable appeal of all three to a largely secular-minded public. They are not concerned to illustrate religious dogmas but to respond to their faith in imaginative and human terms," according to Cruickshank.

So which novels are particularly worth reading? I'll post some reviews another time but here are the ones Cruickshank recommends.

Among Mauriac's "more orthodox, charitable, and explicitly Christian novels of his 'second period'", he praises The Knot of Vipers and The Woman of the Pharisees. (I'm giving the English titles though he gives the original French ones.)

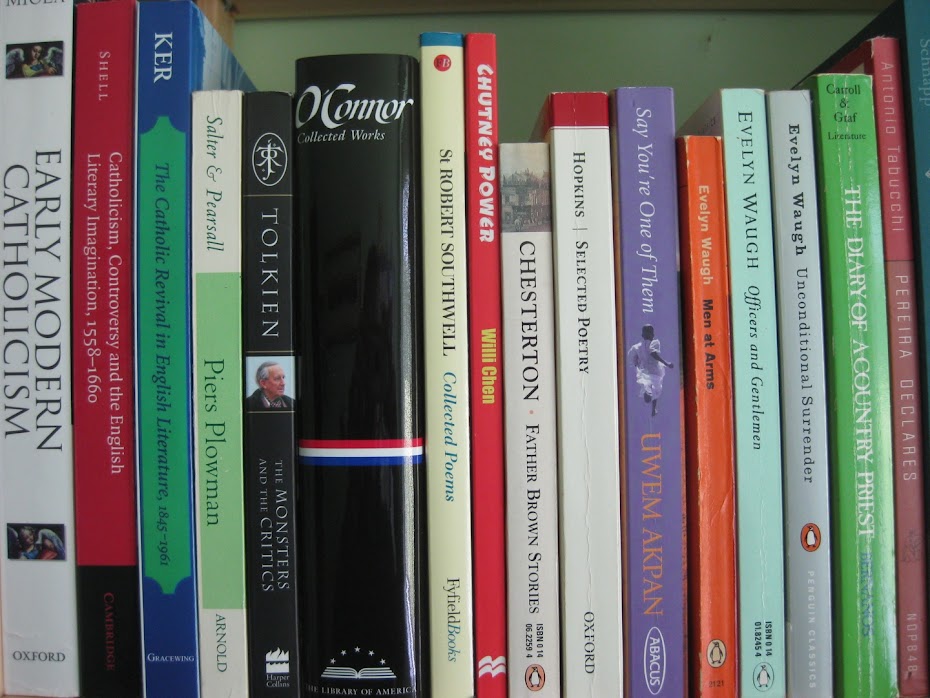

"In some ways, Nouvelle Histoire de Mouchette is Bernanos's most satisfactory artistic achievement with its deeply compassionate account of an unloved, and superficially unlovable, child. The religious significance is implied rather than stated positively, yet implied with both delicacy and boldness, as the suffering of a fourteen-year-old girl points to Christ's passion," according to Cruickshank. However, he also recommends The Diary of a Country Priest and Monsieur Ouine.

As for Julien Green: "The main novels written by Green the believer are Moïra (1950) and Chaque homme dans sa nuit (1960)."

So we can learn from the French but what about the Americans? Well, Cruickshank's comments about Bernanos's use of 'Realism' to mean "responsiveness to the life of the spirit as well as of the flesh", a responsiveness which "must encompass both the seen and unseen worlds" reminds me of Flannery O'Connor's claim that, “All novelists are fundamentally seekers and describers of the real but the realism of each novelist will depend on his view of the ultimate reaches of reality.” ('The Grotesque in Southern Fiction')

And the other American? Julien Green himself. One of the greatest writers in French in the Twentieth Century was actually an American citizen.