I am currently working on a more detailed article about Catholic English teaching but here are my ideas in miniature, in an article for 'Networking - Catholic Education Today', Volume 11, Issue 3, February 2010.

Creating a Catholic English Curriculum

In an important booklet published by the Centre for Research and Development in Catholic Education (CRDCE), four authors, including the editor of this magazine, asked whether there “can be a Catholic School curriculum?”[i] Given that their answer was “yes” (though they were more guarded and nuanced than my one-word summary suggests), what I want to do in this article is begin to map out what the basis of a Catholic English curriculum might be.

Neither I nor any of the authors of the CRDCE booklet wish to create an English Catholic ghetto, nor would we be able to even if we wanted to. The constraints of the National Curriculum and the requirements of public examinations ensure that we cannot approach the teaching of English in schools from a narrowly confessional perspective.

However, practical considerations apart, there are several other reasons why a Catholic English curriculum must necessarily focus on more than just Catholic literature. First and foremost, as John Henry Newman recognised 150 years ago, “English Literature will ever have been Protestant.”[ii] Whether we like it or not, the fact is that most English literature is not Catholic and never has been.

For three hundred years or more, Britain was solidly Protestant and its literature reflects this basic fact. Nonetheless, as G.K. Chesterton once wrote in a typically forthright riposte to Newman’s essay, “The name of Chaucer is alone enough to show that English literature was English a long time before it was Protestant.”[iii]

Indeed, it is arguable that one of the great weaknesses of the English curriculum in schools today is its almost total neglect of any pre-Shakespearean literature. A starting point for the revival of an English Catholic curriculum, therefore, might be the recognition that English Literature began some thousand years before 1564. I am not suggesting that our students should study Old English (though it’s not as daft an idea as it might at first sound) but I am suggesting that there is a place in the curriculum for some of the classics of our pre-Protestant past.

We should not dismiss the work of Catholic authors simply because they wrote along time ago. Pope Benedict was not talking about English literature when he described the hermeneutic of continuity but his insights can clearly be applied in the English classroom.

Some may baulk at the idea of teaching such apparently inaccessible texts but I would argue that Old English and Middle English literature is no more inaccessible than Shakespeare, especially when it is taught in translation and in conjunction with more recent works. Kevin Crossley-Holland, J.R.R. Tolkien and Seamus Heaney, in their very different ways, have all shown how the world of Anglo-Saxon literature can be revived in a form that is fully comprehensible to modern readers.

Such literature does not need to be taught in isolation. The Middle English ‘Pearl’, for example, could be taught in conjunction with Tolkien’s ‘Leaf by Niggle’ while, for the more daring, ‘Piers Plowman’ could be taught alongside Derek Walcott’s ‘The Schooner Flight’.

A thematic approach is also possible. An interesting scheme of work about the afterlife could easily be constructed around Claudio’s speech from ‘Measure for Measure’[iv], the last chapter of Julian Barnes’s A History of the World in Ten and a Half Chapters, Miroslav Holub’s ‘Death in the Evening’[v], Nina Cassian’s ‘Ghost’[vi], passages from the Book of Revelation, as well as some of the Old and Middle English classics.

Part of the problem, of course, is teaching the teachers. How many, I wonder, have studied Middle English or Old English literature at university, even in translation? If the Reformation is the starting point for the teachers then what hope do the children have?

Newman’s assertion is not the final word then, especially as we are now more aware than he perhaps was of the ideological judgments and prejudices that went into the forming of the English literary canon. We have rightly recovered the female and non-English voice in English literature, but we have been slower to re-evaluate the place of Catholic literature in the English canon.

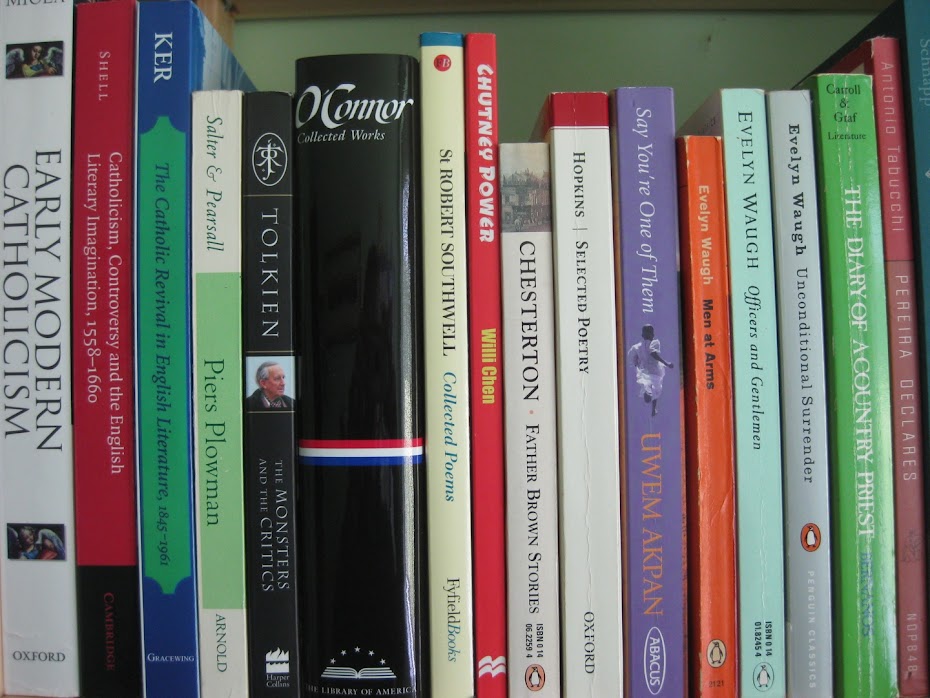

This is not to say that no work has been done in this field. Literary scholars such as Alison Shell, for example, have started to demonstrate the fundamental strength of post-Reformation Catholic literature in much the same way that Eamon Duffy and others have enabled us to see the fundamental strength of the pre-Reformation Church in England.[vii]

Some teachers may feel uneasy about this rewriting of literary history but the point is that we filter what we teach already. The most blatant anti-Catholic diatribes are already expunged from the curriculum, if not from the history of literature. Nobody teaches Thomas Middleton’s A Game at Chesse or Thomas Dekker’s The Whore of Babylon any more.

Indeed, one could go further and argue that Donne, Herbert and, above all, Shakespeare are taught, at least in part, because their religion is, or appears to be, a thoroughly modern, reasonable one. Their poetry conjures up what C.S. Lewis once called “a sweet, Protestant world”[viii], a world apparently free from religious intolerance and bigotry.

By contrast, authors like Thomas More and Robert Southwell – St Thomas More and St Robert Southwell – don’t get a look in because, through no fault of their own, they remind us of precisely such an era. Our English curricula are weaker without them.

Far from imposing our views on our students, we are failing in our duty if we do not teach them to cast a critical eye over the English literary canon. If we teach Shakespeare and the Metaphysical poets then surely we should also teach More and Southwell? If we teach Milton and Wordsworth then surely we should look at the work of Dryden and Pope too? If we are going to teach Hardy, George Eliot and the Brontës, surely we should find some place, at least in passing, for Newman?

Newman’s wise words in The Idea of a University remind us that we cannot simply replace the Protestant past with a Catholic one. However, the truth is that we are much more likely to go along with the marginalisation of our Catholic authors than we are to overturn the English curriculum altogether.

Fortunately, the Catholic English teacher’s task becomes much easier when we reach the 20th century. The children’s fiction of Rumer Godden and Frank Cottrell Boyce, the poetry of Michael Symmons Roberts and Les Murray, the short stories of Flannery O’Connor and G.K. Chesterton are all readily accessible. We have Catholic literature in abundance and do not need to restrict ourselves to the novels of Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene.

Nor, indeed, do we need to restrict ourselves to literature written in England. One simple way of reviving the Catholic English curriculum is to draw upon Catholic literature from around the world. There may not be much teaching of the Nobel Prize-winning Catholics, Sigrid Undset, François Mauriac and Heinrich Böll, in our schools but there is no reason why they should be ignored entirely.

However, there are plenty of other writers to choose from. Uwem Akpan, a Nigerian Jesuit, for example, has swept all before him with his debut collection of short stories, Say You’re One of Them.[ix] With the recent endorsement of Oprah Winfrey, his star is sure to rise still further.

Another quite different Catholic author is Willi Chen, a Trinidadian of Chinese descent, who is a baker, painter and church designer, as well as an author. Chen may not have the same range as Akpan but his short stories could certainly find a place in any school curriculum. The Christmas stories in Chutney Power and Other Stories[x], for instance, offer a wonderful Caribbean alternative to yet more versions of A Christmas Carol.

We don’t need to restrict ourselves to English-language authors, though their works are more readily available. Asian Catholics have suffered from severe publishing neglect but the works of the Indonesian priest, novelist, architect and political activist, Yusuf Bilyarta Mangunwijaya, and the Japanese novelist, Ayako Sono, are well worth seeking out.

Japan also offers some fine non-fiction. In The Bells of Nagasaki, for example, the radiologist, Takashi Nagai, describes the moments immediately before and the days after the dropping of the atom bomb on Japan’s most Catholic city.[xi] There is plenty of Catholic literature out there if we want to teach it.

However, we cannot allow ourselves the comfortable illusion that all is well elsewhere. As Newman wrote in that same essay, “other literatures have disadvantages of their own … One literature may be better than another, but bad will be the best, when weighed in the balance of truth and morality.”[xii] Catholic literature from the rest of the world can complement literature written within the narrow confines of our country but it can never entirely replace it.

I have been writing so far as though English and English Literature were synonymous. However, it is quite clear that there is much more to the English teacher’s job than the teaching of literature. Whether there can be a specifically Catholic approach to English language teaching is much less self-evident.

Our starting point needs to be an awareness that language, and the teaching of language, is never a neutral activity. Nowhere has this been more apparent than in recent debates about the translation of the liturgy into English. Language is contentious, which is why part of the English teacher’s job is to make students aware of its persuasive and propagandist power.

It is easy to discuss jargon in class, to have a lesson on euphemisms, to expose military obfuscation, but perhaps we should also not be afraid to venture into the realm of ethical debate. “Assisted dying”, “dignity”, “terminations”, “emergency contraception”: all these, and very many more, are highly loaded terms which are too often taken at face value. As Catholics in an overwhelmingly secular culture, we need to protect our students from insidious misuse of the language.

There is more to the English language, though, than the power to deceive. I once attended a Welsh evensong at which Rowan Williams preached (in English). He spoke about the Tower of Babel and endangered languages, arguing that the glory of the God is so great that no single language can do justice to Him.

He was speaking about so-called minority languages but his argument holds true even if we limit ourselves to English. The full resources of the English language are not enough to describe the wonder of God and his creation but, if we help our students widen their vocabulary and broaden the range of their expressive powers, we can at least make a start.

There is, then, a great deal more to the Catholic English curriculum, I would argue, than “some critical enjoyment of Christian and catholic poetry and novels”.[xiii] Indeed, there is more to it than the study of Catholic literature and the development of a Catholic approach to English language teaching. Ultimately what is required is the development of a Catholic imagination.

It is entirely possible, for example, to study Chaucer with a 20th century mindset. The Chaucerian narrator so easily becomes a proto-Protestant, a Lutheran looking for a church door on which to pin his theses, rather than a devout pilgrim who was able to poke fun at abuses in the Church because he took the place of the Church in life for granted. It is easy to read Hopkins’ poetry for the music and to ignore the theology. It is easy to buckle under the secular, liberal consensus.

However, if we take our Catholic English heritage seriously, if we allow Catholicism to creep out from the RS classrooms, if we develop a Catholic approach to the language itself, we can help our students develop a Catholic imagination that will serve them well for the rest of their lives.

If we cherish our faith, we cannot but allow it to enter into every aspect of our lives and that includes our schools and our curricula. It will take more than a short article to tease out exactly what that might mean in practice but I offer these brief thoughts, if nothing else, as a means by which to continue the debate.

[i] Can There be a Catholic School Curriculum: Renewing the Debate (Centre for Research and Development in Catholic Education: 2007).

[ii] John Henry Newman, The Idea of a University (Longmans, Green and Co: 1947), 272 [First published, 1852].

[iii] G.K. Chesterton, The Thing (Sheed & Ward: 1929), 236.

[v] Mirsolav Holub, Selected Poems (Penguin, 1967).

[vi] Nina Cassian, Life Sentences: Selected Poems (W. W. Norton & Company, 1997).

[vii] Alison Shell, Catholicism, Controversy, and the English Literary Imagination: 1558–1660 (Cambridge University Press: 1999); Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altar: Traditional Religion in England, 1400-1580 (Yale University Press, 1994).

[viii] C.S. Lewis, That Hideous Strength (Pan Books, 1983), 20.

[ix] Uwem Akpan, Say You’re One of Them (Abacus, 2008).

[x] Willi Chen, Chutney Power and other stories (Macmillan, 2006).

[xi] Takashi Nagai, The Bells of Hiroshima (Kodansha Europe, 2007).

[xii] John Henry Newman, The Idea of a University (Longmans, Green and Co: 1947), 273-274.

[xiii] Can There be a Catholic School Curriculum: Renewing the Debate (Centre for Research and Development in Catholic Education: 2007), 35.

.gif)