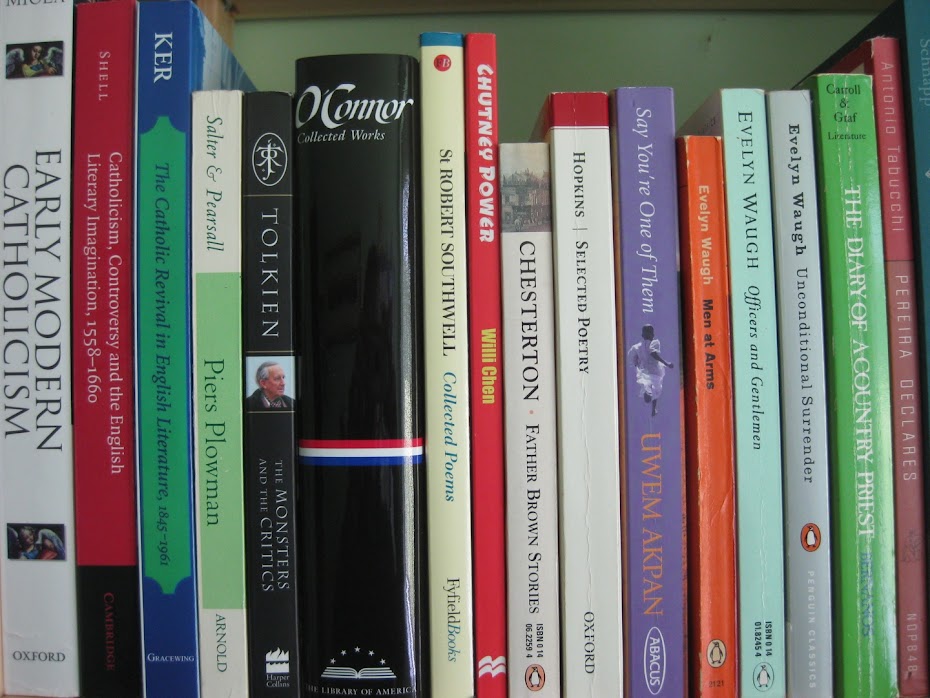

In the introduction to his book about Dostoevsky: Language, Faith and Fiction, Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, writes about "Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene (at least in much of his earlier work) as Catholic novelists, and we mean by this not that they are novelists who happen to be Catholics by private conviction, but that their fiction could not be understood by a reader who had no knowledge at all of Catholicism and the particular obligations it entailed for its adherents. Quite a lot of this fiction deals with what it is that makes the life of a Catholic distinct from other sorts of lives lived in Britain and elsewhere in the modern age. ... Some of it is about how the teachings of the Catholic Church, difficult and apparently unreasonable as it seems, is obscurely vindicated as the hand of God works through chaotic human interactions."

That last sentence is enough to make the hackles rise but, even if we discount it, Williams' definition seems rather curious. These novelists are Catholic but not catholic. They are defined by their differences. Their vision is narrow.

But surely that is simply not the case. Both Greene and Waugh are read and enjoyed by many readers who have very little interest in, sympathy for, or knowledge of, Catholicism. As Catholics, their vision was wide enough to take in everything from gang warfare to relics, from politics to humour, from heaven to hell and everything in between.

This is precisely why Greene so disliked being labelled as a "Catholic novelist". But, if we are to reach towards a Catholic theory of literature, we have not only to be catholic in our own reading (as I suggested in my last post) but we have to allow Catholic novelists (and poets) to be catholic too. If Catholicism means anything at all it means everything.

To be fair to Williams, he does at least identify another type of Catholic novelist - represented by Flannery O'Connor, Walker Percy, Muriel Spark, and Alice Thomas Ellis - whose books are less obviously Catholic but whose "work is about the possibility of any morally coherent life in a culture of banality and self-deceit." Williams feels more at home with this second group but, in using them as a way into Dostoevsky, he surely does a great disservice to Greene and Waugh.

But I mustn't end on a negative. It is encouraging to English teachers everywhere that both the Pope and the Archbishop of Canterbury are prepared to spend time reading and writing. In fact Rowan Williams thought this one was so important that he took a sabbatical to write it.

If you want to read more about his book click here or here or here.

But surely that is simply not the case. Both Greene and Waugh are read and enjoyed by many readers who have very little interest in, sympathy for, or knowledge of, Catholicism. As Catholics, their vision was wide enough to take in everything from gang warfare to relics, from politics to humour, from heaven to hell and everything in between.

This is precisely why Greene so disliked being labelled as a "Catholic novelist". But, if we are to reach towards a Catholic theory of literature, we have not only to be catholic in our own reading (as I suggested in my last post) but we have to allow Catholic novelists (and poets) to be catholic too. If Catholicism means anything at all it means everything.

To be fair to Williams, he does at least identify another type of Catholic novelist - represented by Flannery O'Connor, Walker Percy, Muriel Spark, and Alice Thomas Ellis - whose books are less obviously Catholic but whose "work is about the possibility of any morally coherent life in a culture of banality and self-deceit." Williams feels more at home with this second group but, in using them as a way into Dostoevsky, he surely does a great disservice to Greene and Waugh.

But I mustn't end on a negative. It is encouraging to English teachers everywhere that both the Pope and the Archbishop of Canterbury are prepared to spend time reading and writing. In fact Rowan Williams thought this one was so important that he took a sabbatical to write it.

If you want to read more about his book click here or here or here.