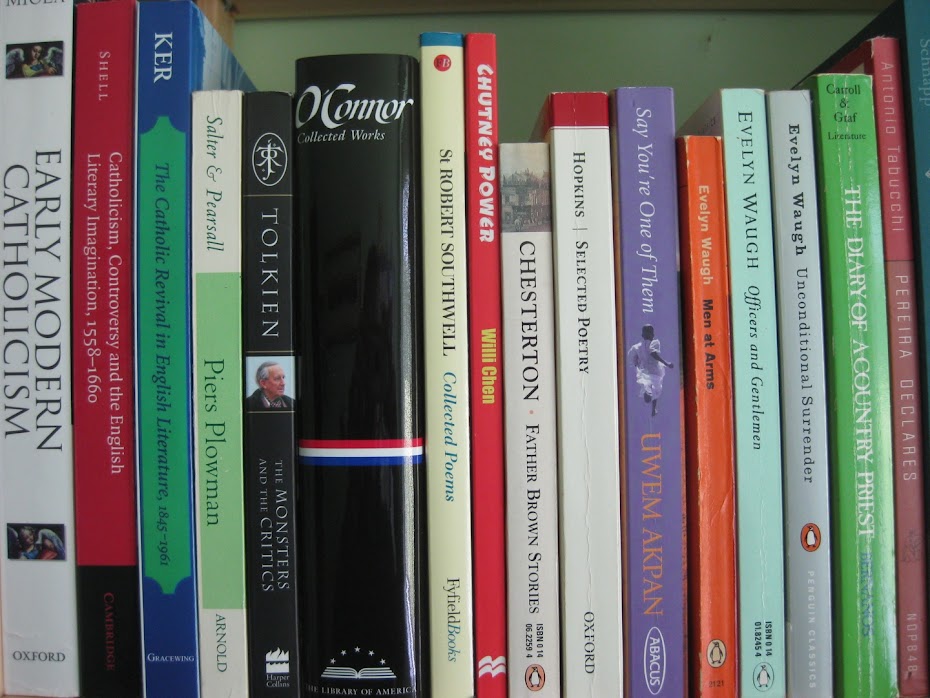

Tolkien rightly distrusted all attempts to find links between authors' biographies and their books, not because such links don't exist but because of their complexity:

"An author cannot of course remain wholly unaffected by his experience, but the ways in which a story-germ uses the soil of experience are extremely complex, and attempts to define the process are at best guesses from evidence that i inadequate and ambiguous." (from the Foreward to The Lord of the Rings)

With that proviso, I'd like to draw attention to this programme from BBC Radio 4:

Novelist Helen Cross, who herself lives in Birmingham, uncovers the story of the young J.R.R. Tolkien, falling in love with Edith Bratt. The love story of Beren and Luthien at the heart of his novel The Silmarillion was inspired by their relationship. They were both orphans, living in a boarding house in Edgbaston, Birmingham. The teenagers would talk out of their respective bedroom windows until dawn, and go for cycle rides to the Lickey Hills. However, when their romance was discovered, Tolkien's guardian, Father Francis Morgan, forbade Tolkien to see Edith until he came of age.Tolkien won an Exhibition to Oxford and Edith went to live in Cheltenham. But at midnight, as he turned 21, Tolkien wrote to Edith saying his feelings were unchanged. Unfortunately, in the intervening years, Edith had got engaged to someone else. Tolkien got on a train and she met him at Cheltenham station. They walked out to the nearby countryside and Tolkien persuaded her to break off her engagement and marry him instead. But the First World War was about to intervene, and Tolkien volunteered and was sent to the Somme.

Helen Cross visits key locations in Birmingham, Cheltenham and Oxford, to tell the story of Tolkien's young life and the love story at the heart of it.

Readings by David Warner as Tolkien and Ed Sear as the young Tolkien.

I'd want to point out that The Silmarillion is clearly not a novel but, nonetheless, it's always worth hearing more about Tolkien and this programme is available online only for five more days.