It is encouraging to see, in the secular press, the argument that "a more nuanced examination of religious belief [than that found in the works of the New Atheists] can be found in modern fiction." However, there are problems too. For a start, Wood takes a long time to get going. Because it is the New Atheists who are deemed to have set the agenda, it takes Wood over 500 words to get to the point where he can write that, "Rather than simply declaring all religious belief to be non-propositional, which is manifestly untrue, it would be more interesting to examine what might be called the practice of propositional beliefs."

Another problem with the article is that it accepts many of the New Atheistic assumptions it criticises. For example, Wood claims that "one good place ... to see religious belief seriously represented and seriously examined, is the modern novel from, say, Melville and Flaubert in the 1850s to the present day. Melville, Dostoevsky, George Eliot, Jens Peter Jacobsen, Tolstoy, Virgina Woolf, Beckett, Camus - and in our own time José Saramago, Marilynne Robinson and JM Coetzee have all shown sustained interest in questions of belief and unbelief".

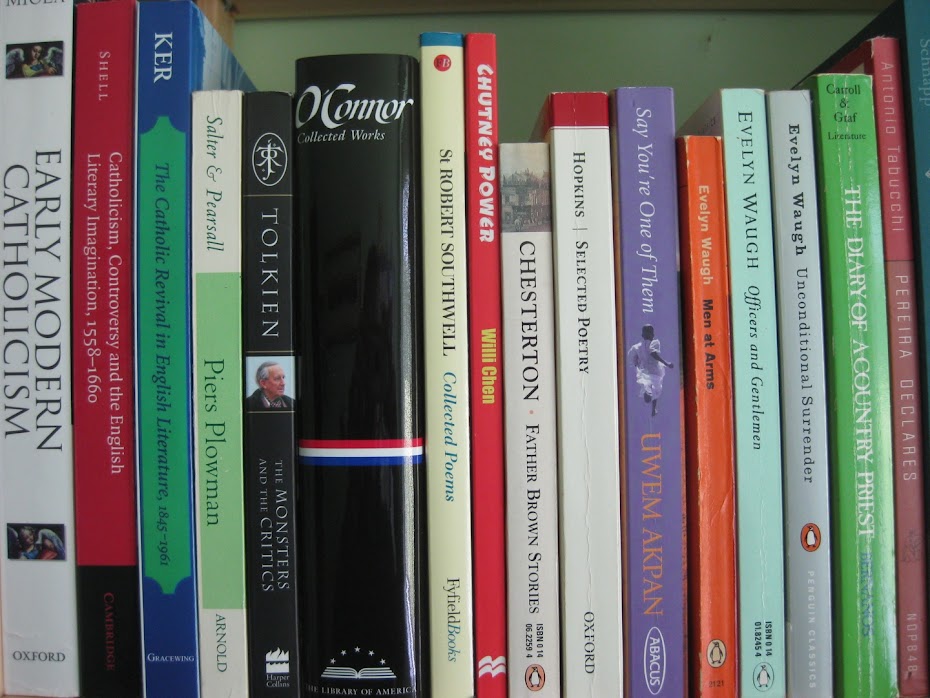

All of which is true but look at the lacunae: Georges Bernanos, Rumer Godden, Graham Greene, François Mauriac, Martin Mosebach, Flannery O'Connor, Muriel Spark, Sigrid Undset, Evelyn Waugh, to name but a few. With the exception of Dostoevsky and Tolstory, who lie safely outside the safe Anglo-American Protestant world, the only orthodox Christian on Wood's list is Marilynne Robinson. And practising Catholics don't get a look in.

The same is true, by the way, of the Weidenfeld lectures themselves, which feature Melville, Jens Peter Jacobsen, Tolstoy, Virginia Woolf and Beckett.

There is an interesting critique of the original lecture in The Oxonian Review in which Tom Cutterham points out, among other things, that, according to Wood, "narrative is both an “ally and a secret enemy” of faith. He connected the rise of the novel with that of a demythologising Christological scholarship in the early 19th century; that is, an interest in a more realistic, historical Jesus, consonant with the conventions of 19th century fiction." But, as I pointed out in my last post, G K Chesterton made a very similar point in 1906, though he drew rather different conclusions. (He also had a lot more to say on the topic than I was able to include in my brief post.) There is more to literature than the modern novel.

Cutterham summarises nicely: "Wood’s central point is not that our secular fiction gets rid of God, and can have no place for him, but that it is precisely in fiction that we can best examine the hold he still has on our consciousness." Exactly. So if we're going to be intellectually open and honest, let's ensure at the very least that we consider what believing novelists have to say about the fluctuations of belief and unbelief too.