The forthcoming papal visit to the UK has brought the life and work of Cardinal Newman back into sharp focus.

As one of the greatest thinkers and writers of the 19th Century, Newman has been horribly neglected in the classroom, perhaps in part because his fiction does not reach the same heights as his apologetic work. However, now is perhaps the time to reintroduce him into the curriculum.

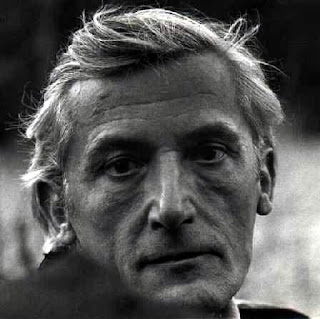

There are some wonderful introductory works by Ian Ker on Newman, including the definitive biography, but the biography is long and life is short, so perhaps there is something to be said for cutting out the middle man and going straight to Newman's writings themselves, especially as The National Institute for Newman Studies has done a wonderful job of putting Newman's work online.

One obvious place to start would be 'The Dream of Gerontius'. Elgar's musical version is now much better known than the original poem but there is enough here to appeal to any student, albeit in a form that will be probably be deeply unfamiliar and initially off-putting.

There was so much to Newman but we have to start somewhere and 'The Dream of Gerontius' is as good a place as any.